UC Food Blog

Addressing nutrition and poverty through horticulture

Nutrition, food security and sufficient family incomes are challenges in many parts of the world. Half the world’s people live in rural areas in developing countries. Because hunger and malnutrition are often linked to poverty, providing economic opportunities through horticultural production not only helps family incomes, but also addresses food security and nutrition. Training women to produce and market horticultural crops in the developing world also helps provide a much-needed income stream for families with children.

UC Davis is addressing food security and economic development in Africa, Southeast Asia, Central America, and elsewhere, by coordinating an international horticulture program. The Horticulture Collaborative Research Support Program (Hort CRSP; pronounced "hort crisp") is one of 10 CRSP programs that focus on global food production and solving food and nutrition problems in developing countries. UC Davis leads the Hort CRSP, with funding support from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

Examples of projects conducted by researchers and educators throughout the world include:

- Inexpensive cold storage systems in rural, developing areas to prolong food longevity; see page 2

- Concentrated solar drying of fruits and vegetables in East Africa; see page 3

- Improving safety and quality of tomatoes in Nigeria; see page 3

- Smallholder flower production in Honduras for export markets; see page 3

The overarching goals of the Hort CRSP are to reduce poverty and improve nutrition and health of the rural poor, while improving the profitability and sustainability of horticulture in the developing world. Priorities in the Hort CRSP include gender equity, sustainable crop production, postharvest technology, food safety, market access, and financing. The program awards research funding in the U.S. and abroad to:

- Realize opportunities for horticultural development

- Improve food security

- Improve nutrition and human health

- Provide opportunities for income diversification

- Advance economic and social conditions of the rural poor, particularly women

Dr. Elizabeth Mitcham, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Sciences at UC Davis and director of the Hort CRSP, notes, “By harnessing the research, training, and outreach expertise of the land-grant universities in the U.S. to work with partners in developing countries, we can improve horticultural capabilities in much the same way that the land-grant system helped revolutionize American agriculture.”

In the three years since the program’s inception, several projects have been completed, and many are ongoing. The program’s website offers a plethora of information, along with newsletters that highlight individual projects.

The program also has a YouTube channel, with videos on Hort CRSP projects. Some of the videos are about projects that are especially important in developing countries, including:

- The TRELLIS project — bringing together graduate students and in-country development organizations; YouTube link

- Using cell phones to give real-time information to growers in rural areas of India; YouTube link

- Inexpensive cultivation practices for smallholder farmers; YouTube link

- Indigenous products increase incomes in Ghana; YouTube link

- Saving indigenous crop seeds in Southeast Asia for resource-poor farmers; YouTube link

UC Davis, ranked first in the U.S. on research related to agriculture, food science and nutrition, and plant and animal science, is positioned to serve global needs related to food and nutrition. Of the 10 CRSP programs administered by USAID, two of the programs are based at UC Davis — the Hort CRSP program, and the BASIS CRSP, which was highlighted in a recent Food Blog post and addresses financial issues related to agricultural productivity.

Cultivating California

Only in California could arid land be converted into the nation’s salad bowl.

In the late 1800s, University of California researchers discovered how to remove salts from the soils of the Central Valley, turning it into one of the most productive agricultural regions.

UC researchers continue to play a key role in agriculture today, keeping California the nation’s leading agricultural state, from dairies in Tulare to nut farms in Newberry Springs.

A new brochure highlights the breadth of UC Agriculture and Natural Resources’ impact. UC guidelines have helped farmers boost broccoli production. UC scientists have developed sweet-tasting citrus and strawberries to meet consumer demands. UC certifies more than 95 percent of wine grapevines grown in the state, providing a reliable supply of high-quality vines for California’s multibillion-dollar wine industry. Whether it’s managing invasive pests, promoting nutrition or sustaining small farmers, ANR serves California’s communities with a focus on advising, educating and searching for solutions.

For more information, read the Cultivating California brochure.

uc anr minibrochure cover s2

Were those the days?

To the tune of Mary Hopkin's iconic 60s hit, Those Were the Days, a team of UC animal scientists ask whether those bygone times people remember nostalgically would be up to the challenge of feeding the world today.

"People have a romantic image of farming in the past," said Alison Van Eenennaam, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the UC Davis Department of Animal Science. "It may be remembered as bucolic, but there wasn't enough food being produced to cope with world population growth."

Van Eenennaam, an expert in animal genomics and biotechnology, rewrote the song and posed the question, Were those the days?, with historical photos of Americans hand-milking cows one by one, preparing a field with a horse-drawn plow and tossing out handfuls of chicken feed from a bucket.

Van Eenennaam's remake declares,

Those were long days, my friend

We thought they'd never end

We'd plow and toil forever and a day

It's not the life we'd choose

We'd work and never snooze

Those were hard days, oh yes, those were hard days.

Interspersed in the video are statistics that reveal how far modern agriculture has come. For example, the U.S. dairy cattle population peaked at 25.6 million animals in 1944. By 1997, improved dairy management and genetics increased milk production per cow by 370 percent, reducing by more than half the number of dairy cows needed to provide milk for U.S. consumers.

The video notes that, in 1923, it took about 112 days to produce a broiler chicken. In 2000, a much larger chicken is produced in 48 days.

"If you're going to expend resources feeding and housing a happy cow," Van Eenennaam said, "it stands to reason that feeding an efficient, high-producing cow decreases the amount of feed required and waste generated per glass of milk or pound of beef."

Van Eenennaam’s video production is competing in a contest sponsored by the American Society of Animal Science. The video that gets the most “likes” on YouTube before June 1 receives a cash prize and will be shown at the American Society of Animal Science meeting in Phoenix. See the video below, but go to YouTube and sign into your Gmail or YouTube account for your “like” to count.

Genetic engineering for roots — not fruits

Even though U.S. consumers routinely buy and eat genetically engineered corn and soy in processed foods — most are unaware of the fact because the GE ingredients are not labeled.

When consumers are asked in surveys whether they would buy genetically engineered (GE) produce such as fruit, most say they would not buy GE produce unless there were a direct benefit to them, such as greater nutritional value.

Yet with continuing invasions and spread of exotic insects and diseases for which there is no known control, the potential importance of trees or vines with some form of genetically engineered resistance is on the rise. In California, such diseases include Pierce's disease in grapes, crown gall disease in walnuts, and the invasive citrus greening (huanglongbing or HLB) in citrus.

"These are potentially devastating diseases to California growers, who produce 70 percent of the fresh fruit and nuts for the entire United States," notes Victor Haroldsen, scientific analyst at Morrison and Foerster, in the current California Agriculture. "They are also a mainstay of the California economy. Fruit and nut tree crops accounted for one-third of the state's total cash farm receipts, or $13.2 billion in 2010."

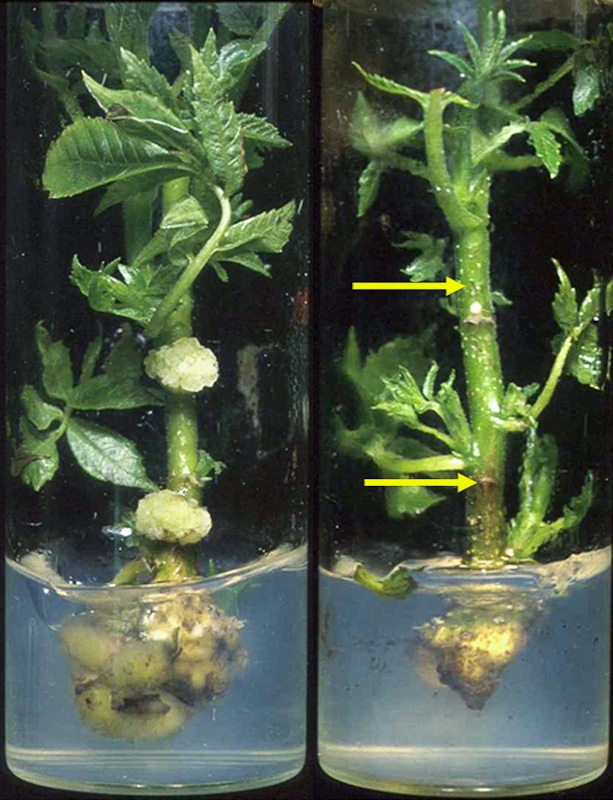

Now, however, Haroldsen reports that there may be a way to satisfy both consumers and growers — called "transgrafting."

"In transgrafting the genetically engineered rootstock can potentially confer the whole plant with resistance to disease. Yet the rootstock does not transfer the modified genes to the fruits or nuts produced," said Haroldsen.

Although over 10 years old, transgrafting technology is just now nearing commercialization, partly due to the long generation times of most trees and vines. Two such transgrafting applications are: a crown gall-resistant walnut rootstock, and a grape rootstock that confers moderate resistance to Pierce's disease.

"The key advantage of transgrafting is that the plant's vascular system can selectively transport across graft junctions the proteins, hormones, metabolites and vitamins from the roots without changing the heritable genes or DNA sequence in the fruit or nut." says Haroldsen.

In recent research at UC Davis, Haroldsen (a former graduate student) and his colleagues confirmed that modified DNA and full-length RNA from the rootstock does not cross the "graft union" into the scion, in the walnut and grape applications, or in a tomato model of these two systems.

"These current GE applications address root or xylem pests and diseases, but future applications will likely target traits aimed at consumer needs such as increased nutritional value or improved flavor," said Haroldsen. "If perceived risks to personal health and the environment could be reduced, genetic engineering could benefit not only growers but Californians around the state," he adds.

The U.S. Farm Bill: What's at stake?

The United States farm bill is up for renewal this year, and what goes into the $400 billion, 5,000-plus page piece of legislation will affect what tens of millions of Americans eat — and don’t eat — in the coming years. On April 5, UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources fired off an enlightening salvo in the public discourse, with a panel of heavy hitters calling on the public to let their voices be heard in the quest to, as panelist Karen Ross, Secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, put it, “move farmers and eaters closer together.”

Looking at the bill’s history, it’s not surprising the two groups have been driven apart. The farm bill was implemented during the Great Depression in the 1930s in order to raise commodity prices and farmers’ incomes, said Gordon Rausser, UC Berkeley professor of agricultural and resource economics and the event’s moderator. The commodities it focused on — food grains, feed grains, dairy, tobacco and peanuts — became political powerhouses while much of the food on our dinner tables — fruits, vegetables, and nuts — were relegated to the category of “specialty crops.”

Broccoli and oranges … specialty crops? “That’s what we grow here in California,” Ross said. And that's what's on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s food plate. In the past 15 years such growers have been taking a more active role in the farm bill to make sure they are not marginalized, she said.

Over eight decades the bill has morphed from a farm to a food bill, the panelists said. Seventy-seven percent of the bill now goes to support the federal Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), the reinvention of the food stamps program.

Ken Hecht, just retired from his position as the director of the California Food Policy Advocates, reeled off some facts about the people who use SNAP:

- 50 percent are working households

- 93 percent are below the poverty level

- 50 percent of benefit recipients are children

- 75 percent are households with children

“There are 1.3 million children who are getting enough to eat because of this program,” Hecht said. “It avoids all those consequences of food insecurity that we all know about: lack of adequate nutrition, lack of adequate health, lack of academic opportunity and performance, lack of social development.” The program not only helps its participants, Hecht, said, but the rest of the people in the community as well.

In addition to SNAP, support for sustainable agriculture emerged as a theme of the presentation. For insight, In Defense of Food author and UC Berkeley journalism professor Michael Pollan offered the audience the perspective of a Martian: we Earthlings are now eating oil instead of eating sunlight. What he referred to as the “free lunch of photosynthesis” was swapped out, starting in the 1940s, for high-yield, industrialized farming that relies on pesticides, machines and giant feed-lots for animals. Pollan said that while farmers were enormously successful in achieving productivity goals, the environmental costs make agriculture second only to cars in fossil fuel production, and the producer of 20 to 30 percent of the country’s greenhouse gases. He recommends a simple criteria should be applied to every provision of the farm bill, from farmers market support to the SNAP program to obscure payment structures: “The question we should ask ourselves is, is this pushing agriculture back onto the sun or is it leaving it on the fossil fuel basis?” he said. “That’s the standard I think we need to apply.”

Ken Cook, president and co-founder of the Environmental Working Group, framed the issue in terms of dollars. “One cotton farmer in 2004 received $2 million. That’s the same amount of money we spent for the entire federal program devoted to organic agricultural research,” he said.

He emphasized the connection between good food practices and good environmental practices, and called SNAP EWG’s number one priority. “We’re trying to inject healthy eating into the farm bill as a legitimate concern of public policy,” he said. He cited a pilot healthy-snack program, in which evaluators noted students who had never seen a pineapple or celery or carrots before. “We should be spending billions of dollars on this program ... getting kids hooked on fruits and vegetables."

Cook pointed out that that much of what drives the farm bill is the politics of committee members securing subsidies for their home states, and conjured the specter of the recent pink-slime debacle to show how effective a little activism can be. Fail to get involved at your peril, Cook, said. “I guarantee you will get more of the same or worse.”

Pollan passed along advice from one of Cook’s staffers: “Simply calling your representative and saying you want more healthy food, you want more environmentally sustainable food, is all you need to do.”

The event was a presentation of the UC Berkeley College of Natural Resource's Spring 2012 Horace Albright Lecture in Conservation. Watch an hour and a half video of the presentations and Q&A: