Winegrapes ripen, unless berry shrivel strikes

August visitors to California wine country can see winegrapes ripening – green changing to gold, red and purple. This is the critical final stage of development, and its success drives one of the state's economic engines, with wine sales generating $18 billion in revenue in 2009. Wine country is also a tourist magnet and a job generator; the industry has a $61.5 billion economic impact statewide each year.

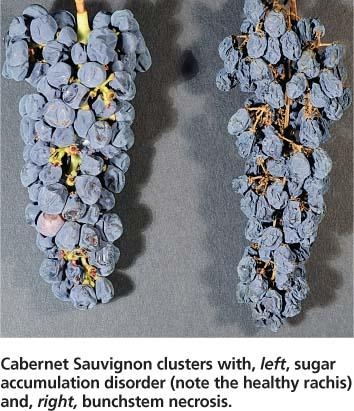

If this is a typical year, California will produce 90 percent of the nation’s wine. In normal vines, the ripening period means sugars and pH increase, while acids (primarily malic) decrease. Other compounds such as tannins develop, and all these factors contribute to the flavors and aromas in the wine that eventually results. (See healthy Cabernet Sauvignon, at right.)

However, in recent years growers have become increasingly concerned about a malady that appears during this phase. Known as “berry shrivel,” this disorder leads to shriveling of berries on a cluster.

There are several kinds of berry shrivel. Of greatest concern to growers and winemakers are sugar accumulation disorder (SAD), in which grapes turn flabby and lack sugar, and bunchstem necrosis, (BSN) in which grapes turn raisin-like on the vine, losing juice and often developing undesirably high sugar content. (See California Agriculture) Either of these disorders makes the fruit less desirable for winemaking, with yield and production losses.

Berry shrivel afflicts both red and white varieties. Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot are the major red varieties to be affected so far. Among the white varieties, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Semillon and Riesling have shown symptoms.

The malady usually becomes apparent when winemakers or sugar samplers are in the vineyard tasting fruit. Once detected, vintners will often make a pass through the vineyard just ahead of the harvest crew to drop this fruit due to its low sugar content and off-flavored juice.

"Berry shrivel usually affects a small proportion of a vineyard's fruit – perhaps 5 percent -- but in particular vineyards and years, shriveling can affect more than half of the crop," says Mark Krasnow, who was a postdoctoral student at UC Davis and is now at the Eastern Institute of Technology in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand. "In some years and some sites, wineries will decide not to harvest a vineyard due to the amount of shrivel. Fortunately this is rare."

The origins of SAD and BSN are a mystery, in spite of research investigations. Krasnow and his colleagues at UC ran a battery of high-tech tests to determine the factors involved, but found little consistency in results and to date, all tests for pathogenic organisms have been negative.

Whether due to SAD or BSN — berry shrivel occurs in vineyards all over the world, managed under different climates, making it a globally significant problem in winemaking.

"The irregularity of when and where (or if) SAD and BSN occur makes them very difficult to study," Krasner notes. Tests conducted by UC Davis Foundation Plant Services were negative for phytoplasmas, closteroviruses (leafroll), fanleaf viruses, nepoviruses and fleck complex viruses.

“It is possible that SAD has multiple causes, and that one of those causes might be a pathogen,” Krasnow says. “In some cases, all the fruit on a vine is affected, even clusters that appear outwardly normal. In other cases, it is only the symptomatic fruit that develops abnormally.”

Preliminary studies suggest that SAD can be propagated by chip budding, but vine-to-vine spread has not been seen, according to Krasnow. Future studies will focus on tests for a causal organism and a more careful examination of the metabolism of fruit affected by this disorder.

Bunchstem necrosis also varies in symptoms and whether effects occur on clusters or whole vines, and can occur at bloom or at ripening (veraison). Future studies will examine varietal differences in susceptibility having to do with xylem structure, the importance of concentrations of mineral nutrients, and other cultural factors.

Comments:

not the same age vines, or the source of vines, different rootstocks but always Cab Sauv.

Frankly less likely in blocks planted with the old FPMS clonal material. More likely with

the newer clonal material like the 337 and such.

Posted by charles k metzger on July 29, 2016 at 1:37 PM