Posts Tagged: citrus

Genetic engineering for roots — not fruits

Even though U.S. consumers routinely buy and eat genetically engineered corn and soy in processed foods — most are unaware of the fact because the GE ingredients are not labeled.

When consumers are asked in surveys whether they would buy genetically engineered (GE) produce such as fruit, most say they would not buy GE produce unless there were a direct benefit to them, such as greater nutritional value.

Yet with continuing invasions and spread of exotic insects and diseases for which there is no known control, the potential importance of trees or vines with some form of genetically engineered resistance is on the rise. In California, such diseases include Pierce's disease in grapes, crown gall disease in walnuts, and the invasive citrus greening (huanglongbing or HLB) in citrus.

"These are potentially devastating diseases to California growers, who produce 70 percent of the fresh fruit and nuts for the entire United States," notes Victor Haroldsen, scientific analyst at Morrison and Foerster, in the current California Agriculture. "They are also a mainstay of the California economy. Fruit and nut tree crops accounted for one-third of the state's total cash farm receipts, or $13.2 billion in 2010."

Now, however, Haroldsen reports that there may be a way to satisfy both consumers and growers — called "transgrafting."

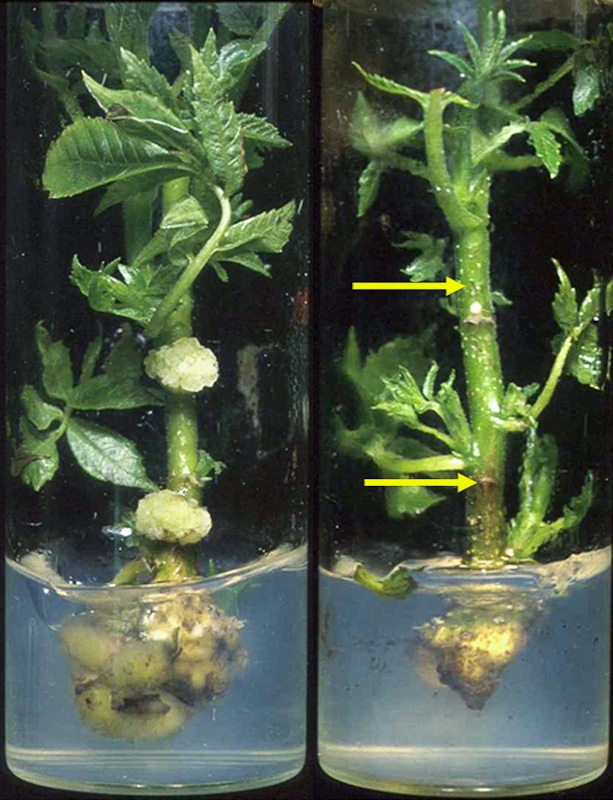

"In transgrafting the genetically engineered rootstock can potentially confer the whole plant with resistance to disease. Yet the rootstock does not transfer the modified genes to the fruits or nuts produced," said Haroldsen.

Although over 10 years old, transgrafting technology is just now nearing commercialization, partly due to the long generation times of most trees and vines. Two such transgrafting applications are: a crown gall-resistant walnut rootstock, and a grape rootstock that confers moderate resistance to Pierce's disease.

"The key advantage of transgrafting is that the plant's vascular system can selectively transport across graft junctions the proteins, hormones, metabolites and vitamins from the roots without changing the heritable genes or DNA sequence in the fruit or nut." says Haroldsen.

In recent research at UC Davis, Haroldsen (a former graduate student) and his colleagues confirmed that modified DNA and full-length RNA from the rootstock does not cross the "graft union" into the scion, in the walnut and grape applications, or in a tomato model of these two systems.

"These current GE applications address root or xylem pests and diseases, but future applications will likely target traits aimed at consumer needs such as increased nutritional value or improved flavor," said Haroldsen. "If perceived risks to personal health and the environment could be reduced, genetic engineering could benefit not only growers but Californians around the state," he adds.

Los Angeles and the “Orange Empire”

An interesting book called “Orange Empire: California and the Fruits of Eden” by Douglas Cazaux Sackman tells the story of how oranges went from being an occasional treat to a mainstream part of the American diet. In fact, Los Angeles was once the center of the “Orange Empire” which developed into a massive industry in California.

Oranges were brought by the Spanish as they settled the missions, and the first sizable grove in Alta California was planted at the San Gabriel Mission, near Los Angeles, around 1804. Oranges were grown on a very limited scale until a frontiersman and entrepreneur named William Wolfskill decided to try growing oranges commercially, using seedlings from the Mission. His initial two-acre orchard was planted in 1841 in what is now downtown Los Angeles. During the Gold Rush, he was able to ship his citrus crop north to miners who were willing to pay a premium to protect themselves from scurvy.

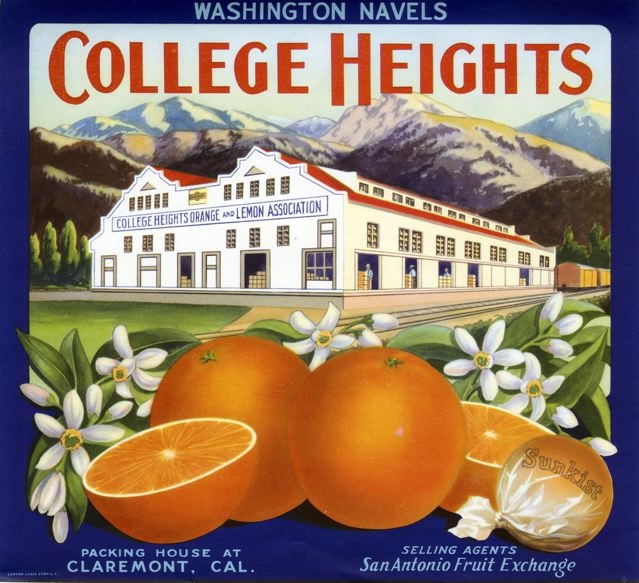

The citrus industry in Southern California grew slowly at first, then really took off in the 1870s due to two innovations. First, a family in Riverside obtained two trees of an orange variety from Brazil. The fruit from these trees was larger, sweeter and easier to peel. This variety, which came to be known as the Washington Navel, created a surge of interest in growing oranges. In the same decade, the transcontinental railroad system connected to Los Angeles, and the very first railcar load of oranges, from the Wolfskill orchard, was shipped east in 1877. In the late 1880s, with the advent of refrigerated rail shipping, the growing citrus industry got another boost. Many new growers entered the citrus farming business, and numerous towns along the foothills of the Los Angeles basin were formed as the industry grew up in those areas.

“Centered on the Los Angeles basin, a vast citrus landscape was coming into being,” said Sackman (p.42). “In 1870, only 30,000 orange trees were growing in the state. Twenty years later, 1.1 million trees were producing fruit." By 1893, local citrus growers had organized themselves into the Southern California Fruit Growers Exchange, which later became known as Sunkist. Sunkist was instrumental in driving the demand for oranges, promoting oranges and orange juice as health aids, with national advertising campaigns beginning in 1907. Sunkist advertisements, along with colorful orange crate labels, helped to brand Los Angeles and Southern California as a new Eden, the land of sunshine and good health. This image helped to drive migration from to Southern California for many years.

Commercial citrus production in Los Angeles County began to decline after World War II, as orchards were rapidly sacrificed to the growing, sprawling suburbs of the Los Angeles basin. As recently as 1970, there were still more than 50,000 acres of citrus in the county; but today, most orange trees in Los Angeles are in backyards rather than in groves.

The citrus industry, still critical to California’s agricultural economy, has long since moved to other counties and other parts of the state. While there is no longer an “Orange Empire” here in Los Angeles, oranges are still a treat, especially if grown in our own backyards. As I prepare for the holidays, I know that today, an orange in a stocking might not be as special as it once was. But to pluck an orange off a tree, on a 75 degree day in December, still makes Los Angeles seem like Eden to a former Midwesterner like me.

Time for a new citrus variety in your backyard?

To me, one of the best things about fall and winter in California is that these seasons herald the beginning of citrus season. Each November, I anxiously await the arrival of the Satsuma Mandarins at the farmer's market, and during their short but delicious season we indulge in a 10-pound bag of the little gems every week.

We have three kinds of citrus growing in our backyard, (sadly no Satsumas), and I secretly enjoy calling family back in Colorado when I know it's snowing to report that we are enjoying juice squeezed from oranges picked from our tree that morning.

If you enjoy growing your own citrus (even without the guilty pleasure of tormenting your relatives) you'll want to check out the new UCANR publication Tried and True or Something New? Selected Citrus Varieties for the Home Gardener. This free, downloadable publication gives side-by-side comparisons of old backyard favorites to newly developed varieties suitable for home growers.

The guide includes ripening information for Riverside, but gardeners in subtropical climate zones statewide can enjoy success with most of these varieties.

From blood oranges to citrons, kumquats to 'Kaffir' limes, there's something different here for every gardener. Hmmmm, I think I need to find a place in our yard for a "Tahoe Gold!"

TriedandTrue

It's a fruit...It's a mandarin...It's ‘KinnowLS’!

On the Jeopardy show, the clues could easily be: “It’s new and attractive. It’s juicy and sweet. And it’s low-seeded and peels easily.”

To which the answer would be, “What is ‘KinnowLS’?”

‘KinnowLS’ – the LS is short for low seeded – is the latest citrus variety released by researchers at the University of California, Riverside.

Large-sized for a mandarin, the fruit has an orange rind color. The rind is thin and extremely smooth. The 10-11 segments in each fruit are fleshy and deep orange in color.

‘KinnowLS’ matures during February through April, and does well in hot climates. It was developed by mutation breeding of the mandarin cultivar ‘Kinnow,’ a mid-to-late season maturing variety developed by UC Riverside nearly 100 years ago. While ‘Kinnow’ has 15-30 seeds per fruit, ‘KinnowLS’ has only 2-3 seeds per fruit.

“People who like very sweet fruit are going to find ‘KinnowLS’ to be very appealing,” says Mikeal Roose, a professor of genetics, who developed ‘KinnowLS’ along with staff scientist Timothy Williams. “When other citrus varieties mature to reach the level of sweetness of ‘KinnowLS,’ their other qualities – such as rind texture – are in decline. Neither ‘Kinnow’ nor ‘KinnowLS’ suffer in this way.”

Yet another attractive quality of ‘KinnowLS’ is that it can be grown in California’s desert regions because the fruit, which matures during February through April, does well in hot climates.

Indeed, ‘Kinnow’ is the most important mandarin in the Punjab regions of India and Pakistan, where ‘Kinnow’ fruit trees constitute about 80 percent of all citrus trees.

“But the fruit, which is popular there, is seedy,” Roose says. “Therefore, ‘KinnowLS’ has very good potential in this area of the world.”

Growers in India and Pakistan will have to wait a few years, however, before ‘KinnowLS’ trees can strike roots there. Currently, plans are to distribute ‘KinnowLS’ budwood, starting this month, to only licensed nurseries in California. (For three years, only California nurseries will be permitted to propagate ‘KinnowLS.’ Licenses for ‘KinnowLS’ propagation outside the United States will be issued thereafter.)

So when will we find ‘KinnowLS’ in U.S. produce aisles?

Alas, not for at least five years. It generally takes about that long to propagate citrus trees.

2602 1hi

Sharing the 'California dream'

We live in an orchard. It’s pretty much like the California dream that Sunkist and the railroads promised to people back East and to dust bowl refugees many years ago – an orange tree in your own backyard! For many of us in the Sacramento region, the dream came true.

Right now the citrus is ripe. Once you start looking, you see it everywhere – bright navel oranges, juicy grapefruit hanging in clusters, glistening lemons and sweet tangerines – some behind fences and some right out front by the street.

Often the trees are big and old, planted long ago. Much of this urban and suburban fruit doesn’t get harvested; people are too busy, the trees get too tall, or there’s just too much fruit to handle at one time. Meanwhile thousands of people in our own community don’t have fruit, fruit trees, backyards or even homes.

Soil Born Farms Urban Agriculture Project is helping Sacramento people share the California dream with their neighbors through the Harvest Sacramento project. Last Saturday I joined a crew of volunteers to pick citrus in Sacramento’s Oak Park neighborhood for donation to the Sacramento Food Bank. I had a great time doing it and met some wonderful folks. The food bank distributes the fruit at mobile food pantries over the next week.

My friend and I arrived at McClatchy Park at 9 a.m. along with a couple of dozen other volunteers. We divided into four or five teams, loaded our vans and pickups with ladders, buckets, picking poles and boxes provided by Soil Born and headed off to the first of three houses whose residents had agreed to let us pick their fruit. Our team included a mom with two enthusiastic children, three young members of Sacramento’s new Green Corps in matching tee shirts, the two of us, and Shannon, our team leader.

Shannon made contact with the resident at the first house, gave us safety instructions, and we got started. We set up ladders and picked by hand and with extendable picking poles with little baskets on the end to grab the fruit. This house had a small orange tree and a large lemon tree in the side yard. We quickly picked a box of oranges, stripping the tree and delivering a few to the front door for the owner to enjoy, then spent about a half hour picking three boxes of lemons from the upper half of the lemon tree, leaving the lower fruit for the homeowners to pick. Then we were off to the next house on our list.

The second house had an awesome huge orange tree and a smaller lemon tree in the backyard, which kept us all busy and yielded another four boxes of fruit. Just a few houses down the street, at our last stop, was the biggest grapefruit tree I had ever seen. We extended the picking poles all the way, set up all our ladders, picked four boxes of grapefruit and left what we couldn’t reach. We took all the fruit back to the park, filling big bins that the food bank picked up, and said goodbye to our new friends. Of course we got to take a few tasty samples of the fruit home with us to enjoy.

Soil Born Farms’ Harvest Sacramento Project will be harvesting fruit in the South Land Park neighborhood on Feb. 19 and in the Curtis Park neighborhood on Feb. 26. Volunteers and donations of fruit that needs harvesting are both welcome. For more information: http://www.soilborn.org/volunteer.html

Harvesting team.

Young picker.