UC Food Blog

Don't blame the Farm Bill for obesity

America’s rising obesity rates are exacting a high cost on society. In looking for solutions, many people blame federal farm subsidies for the current obesity problems. The Farm Bill is up for reauthorization this year. As Congress considers changes, I think it is important to understand that the Farm Bill is not to blame for America’s increasing weight gain.

It may seem obvious that subsidies make certain foods cheaper, therefore contributing to overconsumption, but every serious analysis of the relationship by economists has found the notion untrue. In fact, U.S. farm policies have had generally modest and mixed effects on prices and quantities of farm commodities; the overall effect on the prices paid by U.S. consumers for food has been negligible; consequently, eliminating farm policies would have a negligible influence on dietary patterns and obesity.

Farm subsidies have at times resulted in lower U.S. prices of some farm commodities, such as certain food grains or feed grains, and consequently lower costs of producing breakfast cereal, bread, or livestock products. But in these cases, the price-depressing (and consumption-enhancing) effect of subsidies has been contained (or even reversed) by the imposition of additional policies that restricted acreage or production. In addition, for more than a decade, about half of the total subsidy payments have provided limited incentives to increase production because the amounts paid to producers were based on past acreage and yields rather than current production. Moreover, for the commodities that are subject to U.S. import barriers, the effect of the policy is to increase farm and food prices domestically, providing a disincentive to consume foods that use these commodities as ingredients. Trade barriers that apply to imported sugar, dairy, orange juice and beef cause the prices of these agricultural commodities to increase, and thereby increase the cost and discourage consumption of foods that use these commodities.

What about corn? Farm subsidies are responsible for the growth in the use of corn to produce high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) as a caloric sweetener, but not in the way it is often suggested. The culprit here is not corn subsidies; rather, it is sugar policy that has restricted imports, driven up the U.S. price of sugar and encouraged consumers and food manufacturers to replace sugar with alternative caloric sweeteners, especially HFCS. Combining the sugar policy with the corn policy, the net effect of farm subsidies has been to increase the price of caloric sweeteners generally, and to discourage total consumption while causing a shift in sweetener use between sugar and HFCS. This discouragement has been enhanced recently by U.S. biofuels policy. The current U.S. ethanol policy benefits U.S. corn growers by driving up the demand for corn as feedstock. This effective subsidy to corn growers much more than offsets any impact of other farm policies that might increase the availability of corn for use in food and livestock feed. So the overall effect of the full set of policies is to make all of the corn-based food products more expensive, not less expensive to consumers.

Even if the effects of policy on the prices of farm commodities were large and in a direction that would contribute to obesity, the ultimate impacts on food prices would be comparatively small. Farm commodities used as ingredients represent a small share of the total cost of retail food products, and this share has been shrinking for all farm commodities over the past three decades. On average the farm commodity cost share is approximately 20 percent, but it varies widely: for grains, sugar, and oilseeds, it is less than 10 percent; for soda, a food product that is often associated with obesity, the share is approximately 2 percent.

U.S. farm policies might well be seen as unfair and inefficient. But whether we like these policies or not for other reasons, their effects on obesity are negligible. Farm subsidies are a red herring in the obesity context just as obesity is a red herring in the context of farm subsidy policy. Our careful quantitative analysis of these issues indicates that U.S. farm subsidy policies, for the most part, have not made food commodities significantly cheaper and have not had a significant effect on caloric consumption. In fact, eliminating all farm subsidies, including those provided indirectly by trade barriers, may, if anything, lead to an increase in annual per capita consumption of calories and an increase in body weight. Farm policies have more likely slowed the rise in obesity in the United States—but any such effects must be small. Compared with other factors, the policy-induced differences in relative prices of farm commodities have played only a tiny role in determining excess food consumption and obesity in the United States.

Julian Alston is a Professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of California, Davis, and a member of the University of California’s Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics.

Food truth that we can eat

What we know about eating, not eating and overeating has been investigated by research universities and university-trained scientists since the 1920s. The Journal of Nutrition began publishing in 1928. Now 2.5 million inquiries each month probe a massive body of knowledge about the nature of our evolving physical and cultural relationship with food, with at least 30 more food and nutrition journals collecting and dispersing this science globally.

The result: Americans spend more time debating what to eat than at any other time in history. The firmly held beliefs of most adults about what should be eaten or avoided have origins in the history of this science. In spite of the intent of this research, and because it is frequently challenged, people are understandably skeptical or easily recruited to the next food fad.

As a food science graduate and later as a campus writer, I have worked smack in the center of a leading food research university for more than a decade. This vantage point allowed me to follow the path of these rivulets of research as they flow through scientific journals and later become diluted by commercial interests. They readily dribble to the media without interpretation or the full context of their intended purpose.

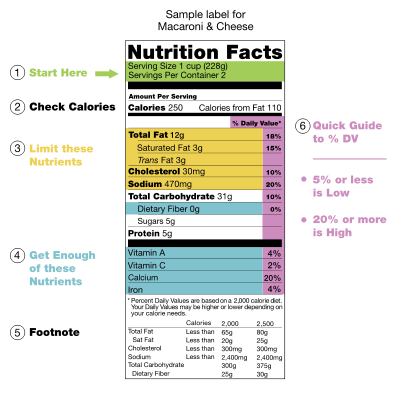

Perhaps the most sacred form of long-term research evidence we follow is the food label, an abbreviated version of truth that empowers our choice to follow our closely held beliefs. University research and methods also indirectly determine what will appear on labels in the future. I have long admired the pragmatic ethics of Barbara Schneeman, who taught me as a professor of nutrition and college dean before going to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to direct the redesign of nutritional food labeling (and other regulations).

Meanwhile, efforts in the national “food court” to hold advertising accountable to the truth are gaining momentum. In spite being misused, universities remain the best source of food truth. This assumes that faculty remains free to challenge the truth and that research funds are available to validate it. Unfortunately, funding for food research is shrinking along with the federal budget, and the federal agencies responsible are seeing an increase in applications for what remains. This week, the National Research Council will release their report , Research Universities and the Future of America: Ten Breakthrough Actions Vital to Our Nation's Prosperity and Security. The report will attempt to list the top 10 actions that Congress, the federal government, states and research universities could take to assure that American research universities help the U.S. “compete, prosper, and achieve national goals for health, energy, the environment, and security in the global community.” Those of us who are watching can only hope that the food truth needed to challenge nutritional hype will be on that list.

Arrival of apricot season

The brief season of apricot harvest is upon us, and many fruit enthusiasts will soon bite into one of these small, delicate, yellowish-orange fruits. I grew up in a San Jose subdivision that was built on an apricot orchard. Each house had 2 or 3 apricot trees left on the lot, and so I have great memories of enjoying them fresh from the tree, still warm from the sun and tartly sweet . But, I have to admit that my favorite form of apricot then and now, are home-dried apricots. They sure were a great treat to find nestled in my trusty red-plaid metal lunchbox in the middle of winter.

Apricots have been grown in the fertile crescent of Persia for thousands of years. The colonists brought the apricot to North America, but most of the stock of today’s production comes from seedlings carried by the Franciscan friars who built the missions and brought much of Spain’s agriculture to California.

In recent years I have heard many disappointed comments at that first bite of a fresh apricot, and I was curious to check with University of California pomologists and USDA Agricultural Research Station specialists to see what progress was being made in bringing more flavorful apricots to consumers. Five different pomologists indicated that market produce buyers tend to primarily value color, size and firmness over the flavor of apricots. The earlier the produce buyers can get them into the grocery store, the more highly they are valued, so they are often harvested before the fruit’s flavor has a chance to develop. The experts I checked with all said they NEVER bought apricots anywhere except a farmer’s market or roadside stand.

The varieties most commonly grown in California are “Patterson”, “Tilton” and “Apache,” and they are selected by growers because of their early harvest dates, large size, attractive color, longer shelf life, and their ability to be used for either fresh or canning applications. Tom Gradziel, a UC Davis professor of genetics and breeding of the Prunus species said, “In the Central Valley, most apricots are still going for processing. Therefore a dual market (processing or fresh) variety such as Patterson is often preferred. It has excellent color, size, and firmness, but tastes like cardboard."

The varieties that the pomologists included in their list of favorites are “Royal Blenheim,” “Robada,” “Katy,” “Primarosa” and “Derby.” Craig Ledbetter, a geneticist working with apricot breeding at the Parlier USDA Agricultural Research Service Center said, “We hear so much about flavor, but I don’t think flavor will be coming to the grocery stores unless in the form of overripe fruit. Here we breed for a sugar/acid balance. We have many breeding selections that taste absolutely fabulous, but are a bit smaller than growers desire. Honestly, they don’t even want to look at ‘small’ fruit. It is a pity!”

Selecting apricots. Apricots do not develop more flavor after they are picked, so select fruit that are completely yellow, deepening toward orange. The subtle, sweet scent of apricot is a good indicator that the inside will taste just as good.

Storing apricots. Keep them on the counter if you will eat them within 2 to 3 days, otherwise store ripe apricots in the refrigerator in a perforated plastic bag.

How to enjoy apricots. Apricots have a pit in the center that is easily separated from the flesh. After washing the fruit, cut in half along the seam and remove the pit. Enjoy the whole fruit, or prepare in tarts, breads, jams, glazes for meats, salsa, or dry them in a dehydrator.

Apricot Tart

Pastry.

1 ¼ c. all-purpose flour

½ tsp. salt

1 Tbls. granulated sugar

½ tsp. almond flavoring (optional)

½ c. unsalted butter, chilled

2 Tbls. Ice water

Using a pastry blender, stir together flour, salt and sugar, cut in butter until dough is in coarse crumbs. Cut in water until pastry holds together when pinched, do not over mix. Lay out a sheet of plastic wrap, form pastry into a ball and wrap with the plastic wrap. Refrigerate 60 minutes. Remove plastic wrap and place on lightly floured surface, roll out to a 12” – 14” circle. Place on a baking tray lined with parchment paper, and return to the refrigerator while preparing the apricot filling.

Apricot filling.

½ c. granulated sugar (or less if the apricots are sweet)

1 Tbls. cornstarch

Dash of salt

1 ½ lbs. (or 10 medium-large) fresh, ripe apricots, pitted and sliced into 1/4” slices

Place sugar, cornstarch and salt into a bowl and stir well, add sliced apricots and toss gently.

Remove pastry from the refrigerator, place apricot filling in the center of the pastry, leaving a 2” border around the edge. Gently fold the pastry border up on top of the apricots, folding the pastry up around the outside edges of the fruit and pinching folds to form a round tart. Seal any cracks in the sides and bottom of the pastry so the juice doesn’t leak out on the baking sheet. Leave the fruit showing in the center of the pastry. Sprinkle with a handful of sliced almonds if desired.

Bake at 375 degrees F for 40-45 minutes, or until golden brown.

Excellent served with vanilla ice cream.

University of California Resources:

- Recommendations for Maintaining Postharvest Quality of Apricots

- Storing Fresh Fruits and Vegetables for Better Taste

- Apricot Information: Fruit & Nut Research and Information Center

Did you catch the buzz?

Did you catch the buzz?

It's still a troubling scene for our nation's honey bees, but it appears that the total losses for the 2011-2012 winter aren't as bad as they could be.

In other words, managed honey bee colonies appear to be holding their own. Overall, they didn't take a sharp dive last winter.

The annual survey, conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Bee Informed Partnership, and the Apiary Inspectors of America shows that the honey bee colony losses averaged 30 percent for the winter of 2011-2012.

Compare that to 34 percent for the 2009-2010 winter, 29 percent for 2008-2009 winter; 36 percent for 2007-2008, and 32 percent for 2006-2007.

Kim Kaplan of the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) of USDA wrote in a May 23 news release that 5,572 beekeepers responded to the survey, which covered the period from October 2010 to April 2011. These 5,572 beekeepers, he said, manage more than 15 percent of the country's estimated 2.68 million colonies.

As ARS entomologist Jeff Pettis, who helped conduct the study, said: "The lack of increase in losses is marginally encouraging in the sense that the problem does not appear to be getting worse for honey bees and beekeepers."

Pettis is a familiar name among scientists, beekeepers and the beekeeping industry. He leads the USDA's chief research agency, the Bee Research Laboratory, in Beltsville, Md.

ARS plans to publish a complete analysis of the data later this year, Kaplan reports, but for now, we know that the average losses didn't fall below 30 percent. Some beekeepers, however, recorded much heavier losses.

Why care about the declining bee population?

As author Norm Gary, emeritus professor of entomology at UC Davis, says in his book, Honey Bee Hobbyist; The Care and Keeping of Bees, "Bees play a fundamental role in food production. About one-third of the food we eat, at least in the United States, can't be produced without pollination by honey bees. Fruits, vegetables, berries, some fiber crops, domestic animal feed, and oil seed crops would be in extremely short supply without honey bee pollination."

And almonds. California, the world's largest producer of almonds, has some 800,000 acres of almonds and each acre requires two hives for pollination. Without bees, no almonds.

"Can you imagine the impact on our food supply and diet if honey bees weren't available for pollination?" Gary asks. "Without them, the human diet would consist mostly of grains and fish."

Think wheat, rice and fish.

No honey, either.

Speaking of honey, you might like to try this Cranberry Oat Bread recipe provided by the National Honey Board. It hasn't been a honey of a winter for the nation's bees, but this is a honey of a recipe.

Cranberry Oat Bread

3/4 cup honey

1/3 cup vegetable oil

2 eggs

1/2 cup milk

2-1/2 cups all-purpose flour

1 cup quick-cooking rolled oats

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon

2 cups fresh or frozen cranberries

1 cup chopped nuts

Combine honey, oil, eggs and milk in large bowl; mix well. Combine flour, oats, baking soda, baking powder, salt and cinnamon in medium bowl; mix well. Stir into honey mixture. Fold in cranberries and nuts. Spoon into two 8-1/2 x 4-1/2 x 2-1/2-inch greased and floured loaf pans.

Bake in preheated 350 degrees oven 40 to 45 minutes or until wooden toothpick inserted near center comes out clean. Cool in pans on wire racks 15 minutes. Remove from pans; cool completely on wire racks. Makes 2 loaves.

Honey bee heading toward pomegranate blossom. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)

Honey bee packing pollen while foraging on almond blossoms at the Harry H. Laidlaw Jr. Honey Bee Research Facility, UC Davis. (Photo by Kathy Keatley Garvey)

Postharvest specialists share their expertise at 'Seed Central'

Aiming to energize the seed industry cluster surrounding UC Davis, Seed Central, an initiative of the Seed Biotechnology Center at UC Davis and SeedQuest, recently highlighted postharvest handling and food safety at their monthly forum. Recordings of invited guest speakers, Marita Cantwell, Trevor Suslow and Roberta Cook, UC Cooperative Extension specialists with expertise in post harvest science, show the passion they feel for their respective subjects and why we're fortunate to have them on our team. Cantwell and Suslow are in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences; Cook is in the UC Davis Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics.

Cantwell, a postharvest physiologist, specializes in handling and storage of intact and fresh-cut vegetables. In her talk, she describes the Postharvest Technology Center itself and gives an overview of the handling challenges of many vegetable varieties.

A plant pathologist, Suslow’s program centers on studying the effects of microflora on the postharvest quality of perishable produce. With much attention to current food safety a priority, Suslow’s produce safety overview and specific case examples help us all (ahem) digest this hot topic.

Cook, an agricultural economist, focuses on fresh produce marketing and food distribution. This presentation centers on North American vegetable markets. Even if you’re not a grower, shipper or retailer, Cook's description of trends in the produce industry are fascinating — we all eat fruits and vegetables every day. She talks about things we might not ever think about.