UC Food Blog

Sustainable agriculture and food systems: An innovative new major at UC Davis

Two terms related to food production — “sustainability” and “food systems” — have been blended into a new major at the University of California, Davis. Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems, the new undergraduate major, in some ways embodies a re-blossomed, student-driven interest in food production, akin to the organic farming movement of the 1970s.

Food systems is a broad term that addresses nutrition and health, sustainable agriculture, and community development. A food system encompasses the entire production chain, not only from farm to fork, but includes broader topics such as short- and long-term impacts on the environment, labor, management of food inputs (e.g., water, pesticides) and outputs (e.g., waste), and the socioeconomic impacts on communities engaged in the food system. In other words, food systems encompasses agricultural production within the broad context of environmental, economic, social, and political concerns.

Neal Van Alfen, dean of the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences at UC Davis, noted during the celebration ceremony for the new major, “Agriculture is incredibly knowledge intensive. It is as knowledge intensive as launching rockets.” He cited a terrarium as a model for how we must maintain a sustainable food production system with limited resources to feed a rapidly growing global population. “The planet is a closed system,” Van Alfen said. “We have to get it right.”

Professor Tom Tomich, master adviser for the major and director of the UC Davis Agricultural Sustainability Institute, said, “The major is about leadership, as much as it is about education. It’s about creating a new generation of leaders who will go on to guide the sustainability transformation for this country and for this planet.” Unlike student programs that are limited to classroom learning, Tomich said that the curriculum for the new major combines the best of three worlds — classroom and labs, the Student Farm, and the real world.

Karen Ross, Secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, attended the opening, along with other high-level state leaders in agriculture, including Craig McNamara, president of the California State Board of Food and Agriculture, and Don Bransford, president of the UC President’s Advisory Commission on Agriculture and Natural Resources.

UC Davis chancellor Linda Katehi, who spoke about UC Davis’s national leadership in sustainability, noted, “This leadership from the state shows the importance of the program and what impact it may have on the state, on us as an institution, and on our students.”

“Agriculture and food have shaped human civilization and are central to well-being and health,” said Ralph Hexter, provost of UC Davis. “We recognize the need to understand both the natural world and our human activities holistically.” Addressing the global significance of the major, Hexter added, “Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems is a major that is truly designed for the 21st century. It responds to today’s needs and incorporates experiential learning and state-of-the-art research.”

A recent UC Davis graduate who helped lay the groundwork for the curriculum, Maggie Lickter, spoke passionately to the 200 people celebrating the major. She said that the major is driven largely by students who have cutting-edge ideas and want to be engaged in creating a useful education. Lickter said that many students felt that components were missing from the traditional agricultural curriculum, such as farming practices grounded in an understanding of ecological systems, and the application of critical thinking skills to modern-day food systems.

In a moving tribute to the success of establishing the major, Lickter said, “This work can’t stop. If you stop stoking romance, love dissolves. If you stop tending a garden, plants wither. So we must stay committed to the evolution of this major.”

Dean Van Alfen, a strong proponent of UC Davis partnerships with the California agriculture industry, views this major as an additional way to create graduates with industry-ready work skills. Addressing UC Davis’s national and global leadership in agriculture, he said, “Agricultural sustainability has been a theme of this campus for a very long time. This new interdisciplinary major is the future in so many ways. It reflects our campus spirit and our culture. It will meet the needs of our stakeholders and the future of our planet.”

For more information:

- UC Green Blog

- Early press release

- UC Davis Student Farm

- UC Davis Agricultural Sustainability Institute

- About the major

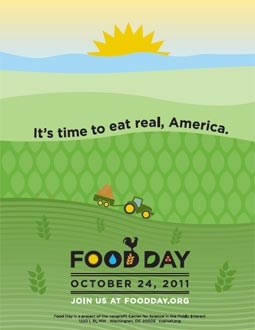

Eat real on Food Day

The first Food Day is coming Oct. 24.

It’s a nationwide campaign with a local flavor: University of California wellness leaders are planning Food Day activities at UC campuses, medical centers and other locations.

The goal is to get people to “eat real,” supporting healthy, delicious and affordable food prepared in a sustainable, humane way.

“We want to raise people’s awareness of where their food comes from. Think every time you put something in your mouth,” said Ginnie Thomas, a health advocate for housing and residential dining services at UC Santa Barbara. She is co-coordinating UC’s Food Day efforts with UC Irvine wellness manager Dyan Hall.

UC Food Day events will include special menus at campus dining facilities; healthy non-perishable food drives for low-income students or community partners; and presentations about mindful eating practices, healthy food preparation and how to build a sustainable food plate. For example, UC Berkeley will host a BYO lunch picnic while UC Santa Barbara events will include meatless Monday for students in residential dining and a registered dietitian discussing mindful eating for staff and students.

Thomas, who used to live on a Ventura County ranch where her family produced homemade butter, cheese and yogurt, encouraged people to follow the six Food Day principles:

• Reduce diet-related disease by promoting safe, healthy foods

• Support sustainable farms and limit subsidies to big agribusiness

• Expand access to food and alleviate hunger

• Protect the environment and animals by reforming factory farms

• Promote health by curbing junk-food marketing to kids

• Support fair conditions for food and farm workers

Food Day is organized nationally by the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer advocacy group known for its studies reporting the unhealthiness of movie popcorn and ice cream shop “coronaries in cones.”

The Food Day advisory board includes UCLA public health professor Jonathan Fielding, UC San Francisco professors David Kessler and Dean Ornish, UC Berkeley journalism professor Michael Pollan, and Chez Panisse owner Alice Waters, a UC Berkeley alumna.

For more information, visit the UC Food Day website to:

• Take the pledge to eat real food that supports any of the six Food Day principles

• Find links to your UC location Food Day calendar of activities (and the UC Food Blog)

• Learn more about Food Day and the six Food Day principles

Good neighbor farming can take the edge off the GMO debate

American grocery stores began selling GMO foods in the 1990s and today stock thousands of items that contain genetically modified corn, soybeans and other crops. To date, no evidence has come to light indicating that foods developed using genetic engineering techniques pose risks greater than food produced using traditional methods.

Still, GMO foods are rejected by a segment of the population. Critics say the long-term effects of eating GMO foods are unknown, that genetically modified genes could flow into weeds or native plants, posing ecological risks, and that higher seed prices for GMO products prevent small-scale producers from competing with large farms. Without mandatory labeling, they find it difficult to avoid products containing GMOs.

UC Cooperative Extension alfalfa specialist Dan Putnam said he is generally in favor of GMO labeling in the United States, “as long as it’s not a warning and not mandatory."

“Consumers should be able to know more or less what they’re eating,” Putnam said.

However, mandatory labeling would raise a number of questions, including what exactly is a GMO?

"Triticale (a forage fed to dairy cows) is a new species, the result of an interspecific cross between wheat and rye, created by humans in the 1950s – a GMO if there was ever one, since it never existed before humans mixed up the DNA," Putnam said.

UC biotechnology specialist Peggy Lemaux suggests a possible alternative to mandatory labeling.

"If there is widespread agreement on the need for labeling, then a market could arise for GMO-free labeled foods for which people would pay extra," Lemaux said. "This would be similar to the current situation with Kosher and organic foods. Since having access to GMO-free foods is not a matter of food safety, but food preference, this approach would lead to a situation in which only those people who want the extra information would pay for it."

The European Union, Japan, Malaysia and Australia currently require labeling on foods that contain genetically modified ingredients. Whether labeling becomes mandatory in the United States or not, supplying food to these countries requires a system for production, separation and traceability of GMO and non-GMO products.

“There is a human factor involved,” Putnam said. “Neighbors have to get along and respect each others’ points of view.”

A reasonable level of tolerance will also help farmers using different production systems to coexist with one another. It is unrealistic to expect 100 percent food purity in a non-GMO food stream, Lemaux said. A small amount of engineered genes in non-GMO food can result from pollen flow or unintentional mingling during post-harvest storage, transportation or food processing.

But coexistence of different varieties and production methods is not new to California food production. Non-GMO farmers can coexist with conventional farmers by using some of the same good-neighbor farming agreements that have long been common in the agriculture industry.

For more information on GMOs in agriculture, see the biotechnology and Roundup Ready alfalfa section on Putnam's alfalfa website and Lemaux's biotechnology website, UCbiotech.org.

Fishing for aquaculture answers

If you buy fresh fish with any regularity you’ve likely come across tilapia. A relative newcomer to American fish markets, the mild, flakey white fish originated in Africa and was introduced to American markets about 10 years ago, sometimes accompanied by favorable sustainability ratings from markets like Whole Foods. Most farmed tilapia consumed in the U.S. currently comes from fish farms in Central America.

“It's a fast-growing fish species that seems more sustainable because it is usually a plant-eater. That is, the fish can survive on plants rather than other fish,” says Alastair Iles, a UC Berkeley assistant professor of environmental science, policy, and management, whose policy research includes studying aquaculture and in particular farmed tilapia.

But sustainability turns out to be a slippery term. “Producing tilapia brings into play a wide range of issues — how developing countries are trying to create sustainable tilapia farming systems but are also struggling with the pollution and waste that they produce,” Iles says.

The scale of the aquaculture industry is expanding around the world, generating, Iles says, a number of environmental and social impacts that cause increasing concern. In addition to the waste problem that fish farms create, feed made from other fish can deplete fisheries even more, and making soy feed may involve land-based agriculture, which could lead to deforestation in countries like Brazil. Escapes of farmed fishes into the wild harm the genetic diversity of the wild tilapia, and there are land use effects as well. As a result, multiple certification schemes are emerging to try to define "sustainable" aquaculture at the global scale.

“It's essential to look at how these schemes are developing because they may affect what the whole industry looks like in the future,” he says.

Iles and his collaborator Elizabeth Havice, an ESPM Ph.D. graduate who is now an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina, are examining two certification schemes that are currently developing: the Global Aquaculture Alliance, the aquaculture industry trade group; and the World Wildlife Fund, working in partnership with the newly formed Aquaculture Stewardship Council.

A new study by the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership, a non-governmental organization, compares the two schemes, and concludes that the WWF certification is tougher in its requirements than the GAA’s standard in that farmers tend to fail the WWF requirements more often. But there is little insight into why and how these differences occur. Is it because the two organizations are using science in different ways — for example, depending on a relatively narrow fish farm-centered impacts analysis, versus using a life-cycle approach that looks at where all the inputs comes from? Or is it because the negotiators of the schemes are aiming at technology-based standards that only large-scale farms can meet?

Iles and Havice focused on the WWF and GGA schemes as most important, examining how they have been developing their standards, which have different requirements. Like the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership study, the researchers are finding that the WWF standard is more likely to be sustainable than the GAA one.

“We think the World Wildlife Fund has paid much more attention to a participatory process and has heard from many more stakeholders, whereas the GAA has been quite top-down,” Iles says. They plan to publish their findings next year.

For now, what’s an environmentally sensitive consumer to do? Avoid farmed fish like tilapia? Iles says that’s not the answer. “We need aquaculture for the foreseeable future because wild-caught fisheries just can't supply enough fish,” he says.

But he stresses that there are very different ways to practice this aquaculture. The new standards, together with Iles’ research to clarify the science behind them, should help navigate the murky waters.

“Our aim is to help improve the science-based process for developing these standards so that aquaculture can evolve into the most genuinely sustainable forms and will actually change how farmers across the world practice their work,” he says.

In the meantime, Iles recommends that if you are buying farmed fish, ask for certification to help ensure that the fish is more sustainable. The new certifications are just beginning to show up in stores, so, watch for them, and demand from your store that they be used.

How Do You Feed a Hungry World?

Like many of us, you may feel completely helpless when you hear of the desperate need for healthful food, especially in the world’s developing nations.

Experts tell us that global population will climb from 7 billion to 9 billion by 2050, and society must face the prospect of dramatically boosting food production while safeguarding the environment.

It’s a challenge of utmost importance to UC Davis’ College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and the theme of a Nov. 5 public program titled “Feeding a Hungry Planet.” The event, to be held in the UC Davis Conference Center, will open with a continental breakfast at 8:30 a.m., followed by presentations from 9 a.m. to noon.

Dean Neal Van Alfen and three faculty experts, featured in the current issue of the college’s biannual magazine CA&ES Outlook, will speak during the morning program. (The magazine is available online at http://caes.ucdavis.edu/NewsEvents/News/Outlook.) Topics will include an overview of global and local food challenges, as well as research on potential solutions involving sustainable agriculture, biotechnology, and the equipping of people in the developing world.

In addition to Van Alfen, speakers will be Beth Mitcham, a postharvest biologist and Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Sciences; Kate Scow, a professor of soil science in the Department of Land, Air and Water Resources; and Alison Van Eenennaam, a Cooperative Extension animal genomics and biotechnology specialist in the Department of Animal Science.

A portion of the $35-per-person registration fee will help support the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Dean’s Circle, an unrestricted fund that enables the college to meet high-priority needs and provide scholarships for students transferring from community colleges.

More information on the Outlook Speakers Series and registration for the Nov. 5 event are available online at http://outlookspeaker.ucdavis.edu or from Carrie Cloud in the dean’s office at (530) 204-7500 or crcloud@ucdavis.edu.

Nectarines in box pic