UC Food Blog

UC student farms seed innovation

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, when organic was a foreign word to most Americans, students at UC Davis and UC Santa Cruz were part of a wave of environmental activism that sought alternatives to agricultural methods that distanced people from farms and relied on heavy use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

In 1971, student enthusiasm for a garden at UC Santa Cruz that used natural cultivation methods grew so much so that 14 acres were set aside for the UC Santa Cruz Farm and Garden to create more opportunities to research and teach organic farming. Meanwhile, a student-led seminar at UC Davis on alternative agriculture mushroomed into a group that lobbied campus administration for land to create a farm that would explore sustainable agriculture. With support from the College of Agricultural and Environmental Science, the UC Davis Student Farm formed in 1977 on 20 acres of what was then a remote corner of campus.

In the decades that followed, these student-led movements helped spur the growth of organic farming and formed the foundations for innovative sustainable agriculture research and education programs at UC Davis and UC Santa Cruz that have served as models for other universities.

Read more and view slideshow at UC Newsroom

Peek inside a UC Master Food Preserver kitchen

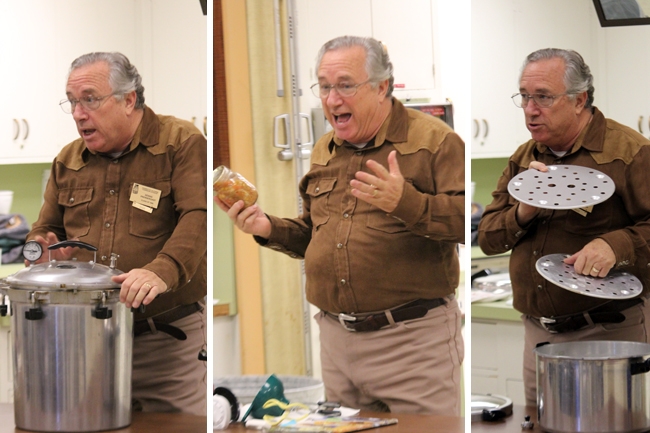

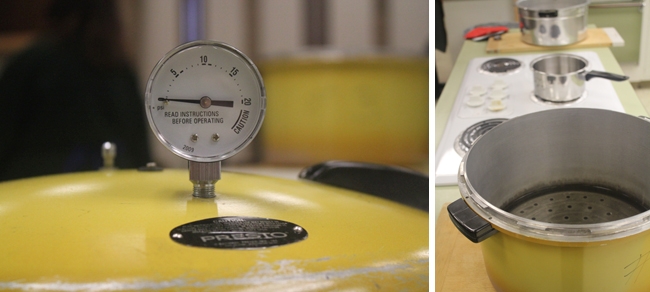

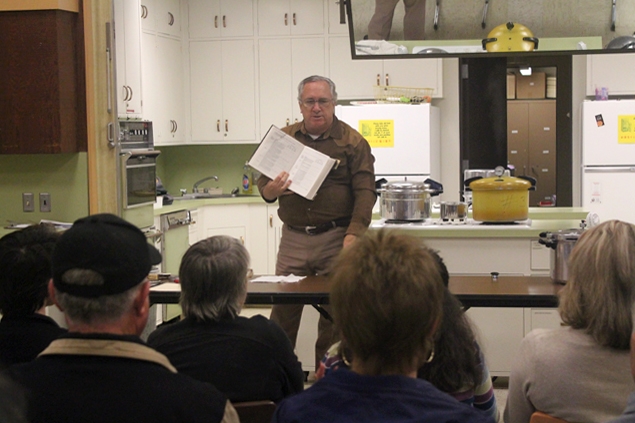

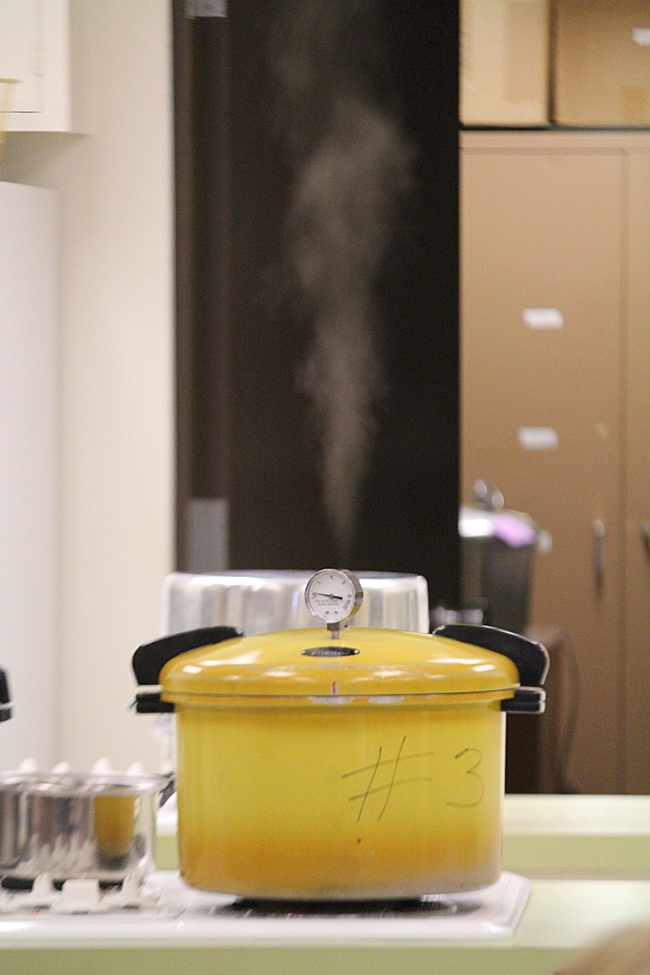

I brought my camera with me to a Master Food Preservers class Saturday at UC Cooperative Extension Sacramento County on pressure canning. In case you’ve been thinking about participating in a Master Food Preservers class, here’s a peek inside the Sacramento demonstration kitchen:

“Cooking is a whole different ball game from canning — a whole different science,” Prendergast said. He's been a UC Master Food Preserver since 1995, and regularly teaches the monthly Saturday morning classes in Sacramento county. Next month's Saturday morning class will be on dehydrating, 10 a.m. to 12 p.m., Dec. 10.

UC Master Food Preservers is a volunteer organization structured in a way similar to UC Master Gardeners. Master Food Preserver candidates complete training to become knowledgeable in food preservation and then are required to volunteer time sharing their knowledge with the public by teaching classes and answering questions.

UC Cooperative Extension currently has Master Food Preservers in four counties:

- Sacramento

- El Dorado (now known as Central Sierra)

- Los Angeles

- San Bernardino

In Sacramento County, the Master Food Preservers offer a monthly class on Saturday mornings that focuses on techniques of a specific preservation process – either water-bath canning, pressure canning or dehydrating. Once a month on Wednesday evenings, the group offers classes that focus on preserving specific fruits or vegetables.

This Wednesday’s class is on “Fall Fruits and Winter Squash” which will include quince and pomegranates among others. The class is 6:30 – 8:30 p.m. at the UC Cooperative Extension office, 4145 Branch Center Road in Sacramento; registration to attend is $3.

Time for a new citrus variety in your backyard?

To me, one of the best things about fall and winter in California is that these seasons herald the beginning of citrus season. Each November, I anxiously await the arrival of the Satsuma Mandarins at the farmer's market, and during their short but delicious season we indulge in a 10-pound bag of the little gems every week.

We have three kinds of citrus growing in our backyard, (sadly no Satsumas), and I secretly enjoy calling family back in Colorado when I know it's snowing to report that we are enjoying juice squeezed from oranges picked from our tree that morning.

If you enjoy growing your own citrus (even without the guilty pleasure of tormenting your relatives) you'll want to check out the new UCANR publication Tried and True or Something New? Selected Citrus Varieties for the Home Gardener. This free, downloadable publication gives side-by-side comparisons of old backyard favorites to newly developed varieties suitable for home growers.

The guide includes ripening information for Riverside, but gardeners in subtropical climate zones statewide can enjoy success with most of these varieties.

From blood oranges to citrons, kumquats to 'Kaffir' limes, there's something different here for every gardener. Hmmmm, I think I need to find a place in our yard for a "Tahoe Gold!"

TriedandTrue

The colorful, healthful pomegranate is a good food and lovely landscape plant

A jewel-toned garnish for California cuisine, antioxidant-rich elixir of good health, drought-resistant tree ideal for desert-like regions in California, the pomegranate has inner beauty and outward resiliency driving its growing popularity.

Pomegranates have been cultivated since ancient times, and are referred to poetically in texts ranging from the Bible to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. They are unusual among California fruit. Tough, leathery skin protects bright red, tart-sweet juice sacs, called arils, which are separated in groups by white spongy tissue. Inside each sac is an edible seed which contains fiber and unsaturated fat. The red pulp is a good source of potassium and vitamin C.

More a large shrub than a tree, with multiple trunks reaching a height of 15 to 20 feet, pomegranates are adapted to regions with cool winters and hot summers. Beautiful shiny foliage and a long flowering season make them attractive additions to coastal, inland valley and desert landscapes. Pomegranates tolerate a wide range of soil types, but prefer deep, well-drained loams. The best time to plant is in late winter or early spring – just before they leaf out.

Data about the scope of California commercial pomegranate production is hard to find. USDA stopped collecting pomegranate data in 1989 and CDFA groups pomegranates with kumquats, loquats, persimmons, prickly pears and other unusual fruit. UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor Maxwell Norton said county pesticide registration data indicate that five Central Valley counties – Kern, Fresno, Madera, Kings and Tulare – have about 35,000 acres planted to pomegranate. About 500 acres are planted in other counties combined. Kern County has the highest production with about 17,000 acres producing fruit valued at $115 million per year.

UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor Paul Vossen suggests the following standard varieties for backyard plantings:

- Ambrosia – Huge fruit, pale pink skin, similar to Wonderful

- Eversweet – Very sweet. Red skin, clear juice. Good for coastal areas

- Granada – Deep crimson fruit color. Matures early, but needs heat

- Ruby Red – Matures late, but not as sweet or colorful as Wonderful.

- Wonderful – Large, deep red fruit, large, juice red kernels. Small seeds.

For eating or juicing, select pomegranates at grocery stores by weight, not color. The heavier the pomegranate, the more juice inside. Some consumers are deterred from purchasing and eating the raw fruit because they believe it’s difficult to prepare. UC Master Food Preserver Geri Scalzi gives five simple steps that make eating fresh pomegranate easy:

- Cut off the top half an inch below the crown. Four to six sections of pomegranate arils divided by white membrane will be visible.

- Score the leathery skin with a sharp knife along each section.

- Break the pomegranate apart along the score lines. This can be done under water to prevent squirting pomegranate juice, which tends to stain clothing.

- Loosen arils and membranes and drop them into water. The arils will sink, the membranes will float. Skim off the membranes with a slotted spoon.

- Pour the arils and remaining liquid through a strainer.

The pulpy seed sacs are then ready to be eaten plain, tossed in salads, stirred into yogurt or sprinkled over cereal.

For more information on pomegranate production, attend a public meeting at the UC Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center, 9240 S. Riverbend Ave., Parlier, from 10 a.m to 1 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 29. The following topics will be covered:

- Insect pest update, integrated pest management entomologist Walt Bentley

- Black heart disorder and tree decline issues, UC Davis plant pathologist Themis Michailides

- Interesting selections in the USDA germplasm collection, USDA national clonal germplasm representative Jeff Moersfelder

- Irrigation, fertigation & nitrogen use efficiency with drip irrigation, Claude J. Phené, USDA-ARS

- Summary of acreage trends, Merced County farm advisor Maxwell Norton

RSVP to Yolanda Murillo at ymurillo@ucdavis.edu or (559) 600-7285. The $10 registration fee may be paid at the door with cash or check. More information.

Are weeds taking over your garden?

My calendar says November but the weeds in my garden think it’s spring. That nice rain last month followed by warm, sunny days has prompted them to grow like, well, weeds and that’s not good news for my winter crops.

What’s a gardener to do?

Like so many other gardeners, I turned to the folks at the UC Davis Weed Science Program. Housed in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, the “weeders” are experts at helping growers and gardeners improve plant production by controlling weeds.

What are the most effective organic tools for controlling weeds? That’s what I, and thousands of others, want to know. You don’t have to be an organic grower to seek organic tools for fighting weeds. Synthetic herbicides come with a cost to growers and the environment, so more and more farmers are seeing the value in employing organic tools with or without other means.

Which tools work the best in which situations? Here’s a quick overview, courtesy of Cooperative Extension Specialist Tom Lanini, who specializes in weed control in vegetable crops.

Mulches – Researchers test them all – plastic, bark, wood chips, other porous material, even what they call live mulches like clovers and fava beans. Mulches block light, which weeds need to grow. “I think mulches can be the best organic option for fighting weeds, especially for vines and trees,” Lanini says. Mulches are also a key weed-fighting component in organic strawberry and many other crops.

Organic sprays – Coverage is the key. “No matter what type you use – oils, soaps, acids, etc. – if you don’t spray-to-wet, 100 percent coverage, the weeds will grow back,” Lanini says. Temperature and the age of the weed matters too. Apply in temperatures above 75 degrees when weeds are very young – about a week old – for best results. Broadleaf weeds are easier than grasses to control with sprays.

The most effective organic spray Lanini has found so far is good old-fashioned vinegar, the kind you use to make pickles. The trouble with that is, the FDA has yet to approve it for controlling weeds. “You can eat it, but can’t spray it on your weeds,” as Lanini says. There are herbicides with vinegar as their active ingredient, but they are much more costly than household vinegar.

Flamers – These propane-fueled devices quickly raise the temperature of the weed to more than 130 degrees, rupturing its cell membranes. Grasses are hard to kill by flaming because the growing point is protected underground. Flamers require quite a bit of fuel, which can be costly.

Solarization has become an important method of weed and disease control in organic desert vegetable crops. In this system, four to six weeks of solar heat under clear plastic film will kill weed seeds and pathogen propagules.

Cultural practices are extremely important in all vegetable crops especially in organic crops. Crop rotations result in shifting environments that do not favor any one weed. Use of preplant irrigation followed by shallow tillage, or flaming is a very effective method of reducing the potential weed infestation during the crop cycle.

Weeding and thinning by tool or machine is a time-honored solution. Never underestimate the value of a hoe.

You can read more about the UC Weed Science Program here and access the Weed Research and Information Center web site here.

For more detail on weed management for organic vegetable crops, Click here.